Dairy Country

a new book dips into the multifarious world of fermented dairy in Central Asia

Hello and thank you for joining me here. This is the occasional free instalment of Journeys Beyond Borders, therefore do share it with anyone who may find it interesting.

~

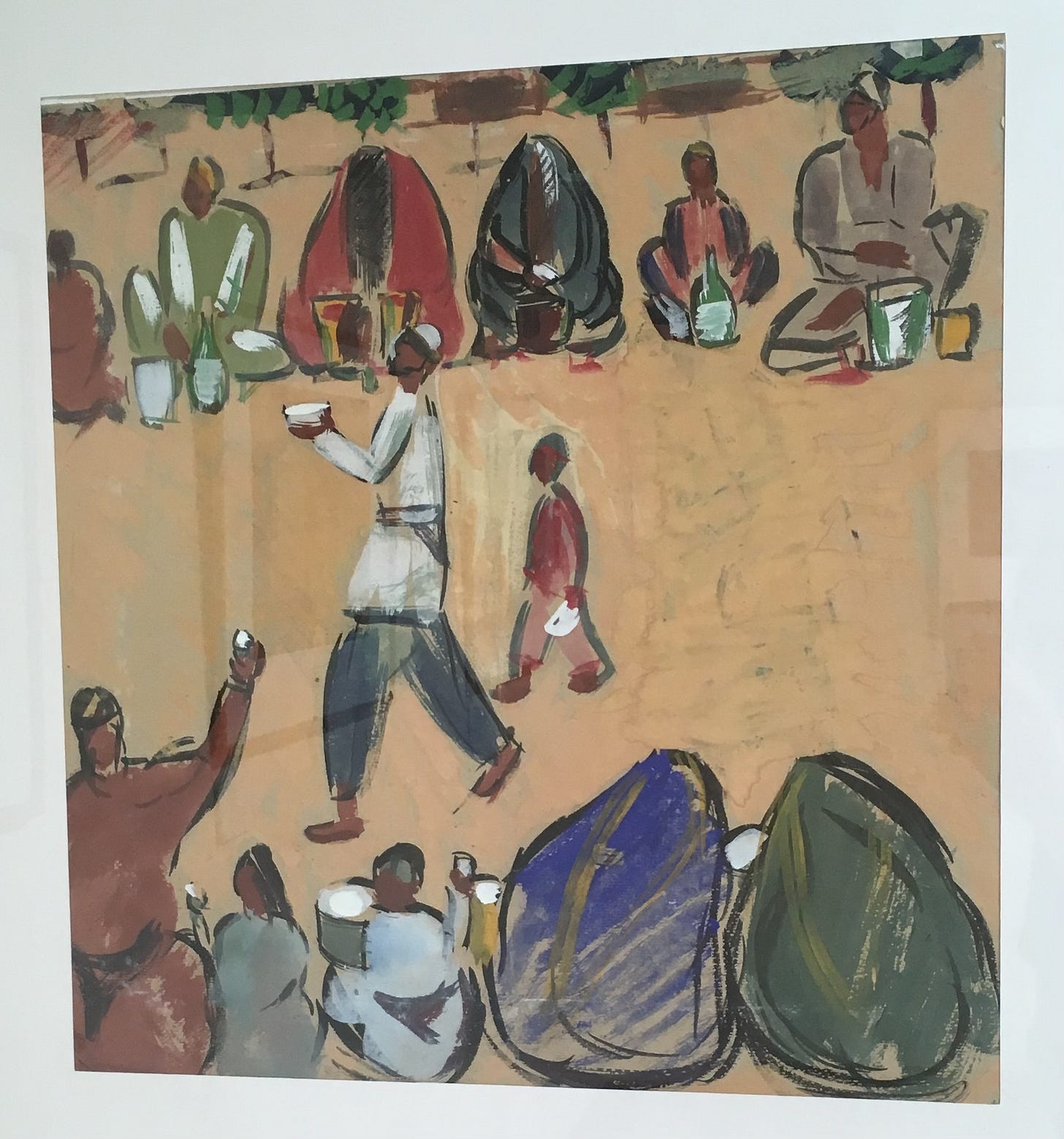

For this week’s, slightly different, Journeys Beyond Borders, I’d like to start with a painting by Ural Tansykbayev, called Milk Bazaar (1932). Long considered to be one of the finest artists of Central Asia, Tansykbayev is experiencing something of a revival with recent exhibitions of his work in Tashkent and Almaty, as well as a mention in the opening paragraph of this New York Review of Books long-read piece by Sophie Pinkham on Uzbekistan’s employment of art and beauty as part of its nation building and soft power.

Still, the best way to see avant-garde Uzbek art, and Tansykbayev’s other masterpieces, is to travel out to the Savitsky Museum, in western Uzbekistan, as I wrote about earlier, here.

Milk Bazaar appeals to me for simple reasons: I like how the bowls and jugs of bright white milk contrast with the dun desert hues and the assortment of dyed fabrics that the sellers and buyers are dressed in.

I also like it for what it might suggest. In 1927, just a few years before the painting was completed, the Soviet Union had officially begun its campaign to ban the burqa (or paranja in Central Asia), so seeing the women in the painting sat wearing them could be a nod to that drive, launched by the Soviets to “emancipate” Muslim women (in order for them to join various workforces).

Why am I telling you about this relatively obscure painting now? Because I thought of it, and Tansykbayev, as I started to read a newly published book, Fermented Dairy of Central Asia, by Dr. Simi Rezai-Ghassemi.

Born in Tabriz, in the Azerbaijan region of northwestern Iran, Simi (also on Substack, here) is a food anthropologist, scholar, linguist, writer and ethnographer.

Her book is timely. Globally, there is growing interest in fermented foods (for example, think of the recent kefir craze, “an extraordinary probiotic, perhaps one of the best sources of beneficial microorganisms to support gut health”, as Simi rightly asserts) and because more people are now visiting Central Asia, especially Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Primarily, Simi’s research aims to trace the transformation of milk into fermented staples while examining the cultural, nutritional, and historical significance of dairy in Central Asia. While it is a scholarly work it is also highly readable with fascinating anecdotes and humour woven throughout.

Mealtimes during my travels through Central Asia over the years have involved milk in many different forms, sometimes fermented, sometimes not: tubs of sour cream, yoghurt, buttermilk, byshtak (a fresh, zingy-tasting curd), foamy kefir, kaymak (thick cream), suzma (strained yogurt), kumis (mildly alcoholic fermented mare’s milk), camel milk, ayran and pyramids of nubbly tvorog (dry, sweetish cottage cheese). You get the idea. There is so much to taste and experience, dairy (fermented or not), is a rich subject for a book.

I have been enjoying Simi’s perspective which challenges some of my own established viewpoints. My first thought, given that Iran features quite a lot in the book, was that, hmm, modern-day Iran isn’t considered by most as ‘Central Asia’ … On this, Simi writes: “Strictly speaking, the Caucasus (where I’m from) does not fall within the geographical concept of “Central Asia.” However, the many designations applied to these lands are fluid and contested. Then there are terms like “Middle East” or “Far East,” derived from their proximity to past colonial European Empires. In this book, “Central Asia” is employed more broadly to denote the expanse stretching from the western frontiers of China to the Caucasus. Likewise, it is used to refer to the interconnected linguistic and cultural spheres of Turkic, Mongolian, and Iranian peoples of Eurasia.” This also makes sense.

But back to the dairy…

In 2022, I wrote a feature for the Financial Times about traditional dairy methods in Kyrgyzstan, and I went to interview Jenish Abykanov and his family in a timber-clad home deep in the Boo-Jetpes gorge.

His mother, Aytbubu, brought out her essential kit for making kumis (fermented mare’s milk): a chanach – a bag made from goatskin that has been smoke-cured over a juniper fire – is essential for flavour. The mare’s milk goes into that, where it ferments, before being beaten in a barrel with a bishkek, the paddle from which the Kyrgyz capital takes its name.

I’d never considered, though, where the word kumis (mare’s milk) comes from. On its origins, Simi writes: “We are not sure where the name for kumis, variously written and pronounced, originates, but from the thirteenth century onward, kumis with different pronunciations became synonymous with fermented mare’s milk in Turkic, Iranian, and Arabic languages. Helga Anetshofer, a Turkic-language specialist, suggests that kumis (which she Romanizes as qimiz) is a wanderwort, meaning “migrant word.”

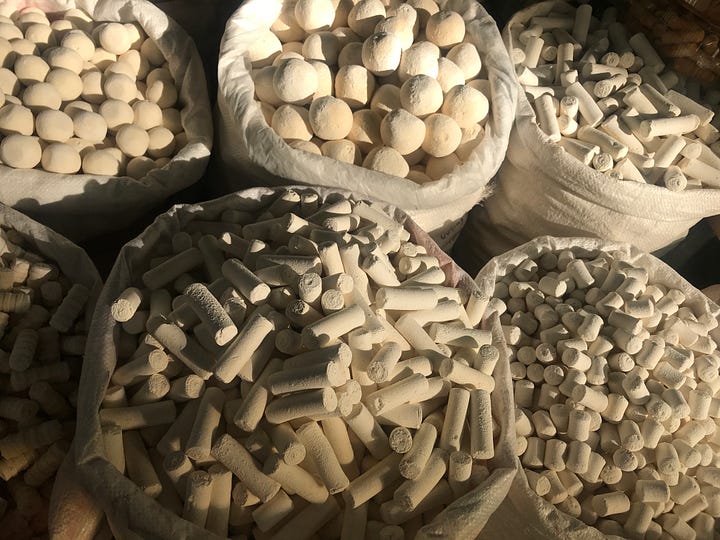

I was immediately drawn to chapter six, too, all about what Simi calls goroot, and I’d call qurt or qurut (as it is called in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), the salty dried milk curds, shaped into spherical gobstoppers, sold in town bazaars but traditionally known as trail food for nomads out on the steppe. How’s this for a description: “dried, lightweight, and portable. She is quite a gal, being credited with fuelling the Mongol conquests and sustaining cosmonauts in space, and she may even have been used as grave goods.”

As well as a movable feast, qurut is a popular beer snack today. I remember well my first taste of these chalky salt bombs when I ordered a plate of qurut alongside a lager in Dushanbe, the Tajik capital, in 2009 at a little stand close to the opera house. I’d never tasted anything quite like it before, and I do still find the saltiness a challenge, but there is no denying that it is an ancient, important and genius food.

Simi writes evocatively about how goroot has long been traditionally prepared in Tabriz, “air-dried on woven baskets so that air circulates around them and they dry out evenly”, though she laments that it is harder to find such practices nowadays: “Today in Tabriz, it is hard to buy this type of traditional dry gooroot. Instead, there are rows of industrially produced and packaged gooroot in paste form, already rehydrated, pasteurized, and ready for use.”

While I have written about Central Asian qurut in my books, I knew next to nothing of the Āzari methods and culture surrounding these little salty treats, but by reading Simi I could picture them so clearly as to almost taste them: “left to air dry, typically outdoors, out of the sun, covered with light gauze to allow airflow while keeping dust and insects away.”

It’s true to say that a good book is like a conversation. A two-way thing, ideally. You read, and digest, what the author has to say but you also feed in your own questions, opinions and memories. Reading Simi’s absorbing book has certainly been a synergic experience for me.

I’m running out of room, so let me finish by saying that you can purchase Simi’s book here - and please do - and if you happen to be near the city of Bath, then head along to the bookshop Topping & Company on 23 April to meet Simi and to buy a copy of her book in person (book your place here). Or, if you can’t make that, do have a listen to the Delicious Legacy podcast, here, where Simi is in discussion with Greek gourmand Thomas Ntinas.

~

Thank you for reading. I’ll be back to you on Monday with another View Finder, which will take the form of a painting paired with a poem. Until then.

Dear Caroline, Thank you for your thoughtful and generous review. I’m truly grateful for the care and insight you brought to your reading, and I feel honoured by the time and attention you gave it. It means a great deal to me to see the book given such a meaningful send-off into the world.